"Mineral rights" entitle a person or organization to explore and produce the rocks, minerals, oil and gas found at or below the surface of a tract of land. The owner of mineral rights can sell, lease, gift or bequest them to others individually or entirely. For example, it is possible to sell or lease rights to all mineral commodities beneath a property and retain rights to the surface. It is also possible to sell the rights to a specific rock unit (such as the Pittsburgh Coal Seam) or sell the rights to a specific mineral commodity (such as limestone).

In most countries of the world, all mineral resources belong to the government. This includes all valuable rocks, minerals, oil and gas found on or within the Earth. Organizations or individuals in those countries cannot legally extract and sell any mineral commodity without first obtaining an authorization from the government.

In the United States and a few other countries, ownership of mineral resources was originally granted to the individuals or organizations that owned the surface. These property owners had both "surface rights" and "mineral rights." This complete private ownership is known as a "fee simple estate."

ADVERTISEMENTFee simple is the most basic type of ownership. The owner controls the surface, the subsurface and the air above a property. The owner also has the freedom to sell, lease, gift or bequest these rights individually or entirely to others.

If we go back in time to the days before drilling and mining, real estate transactions were fee simple transfers. However, once commercial mineral production became possible, the ways in which people own property became much more complex. Today, the leases, sales, gifts and bequests of the past have produced a landscape where multiple people or companies have a partial ownership of or rights to many real estate parcels.

Most states have laws that govern the transfer of mineral rights from one owner to another. They also have laws that govern mining and drilling activity. These laws vary from one state to another. If you are considering a mineral rights transaction or have concerns about mineral extraction near your property, it is essential to understand the laws of your state. If you do not understand these laws, you should get advice from an attorney who can explain how they apply to your situation.

Surface coal mine: Large mining trucks are loaded with coal at this surface mine. Here two thick coal seams are being removed. Surface mining involves stripping away all overburden (rock and soil above the coal seam), removing the coal, replacing the overburden and revegetating the land. Surface mining completely disturbs the land and produces a new landscape. It can be done when coal seams are close to the surface. Depending upon coal quality and other factors, about ten feet of overburden can be removed for each foot of coal. Image copyright iStockphoto / Rob Belknap.

"I'll pay you $100,000 for the coal beneath your property!" This type of transaction has happened many times. The fee simple owner may not have the interest or the ability to produce the coal beneath his property but a coal company does.

ADVERTISEMENTIn this type of transaction, the owner wants to sell the coal but retain possession and control of the surface. The coal company wants to produce the coal but does not want to pay an additional price to acquire the buildings and the surface. So, an agreement is made to share the property. The original owner will retain the buildings and rights to the surface, and the coal company will acquire rights to the coal. The transaction can involve all mineral commodities (known or unknown) that exist beneath the property, or, the transaction can be limited to a specific mineral commodity (such as "all coal") or even a specific rock unit (such as the "Pittsburgh Coal").

Underground coal mine: When the coal is too deep to surface mine, a mining company will build an underground mine. They can tunnel into the coal seam or drill a large shaft down to the mining level. These shafts are large enough to lower mining equipment and workers into the mine and remove coal. Extra shafts must be built to ventilate the mine. Underground mining can damage the surface because the rooms and passages usually close through collapse or settlement over time. Sometimes the damage occurs after responsible individuals are dead and the mining companies are defunct. Thus, no one to sue. Or, the contract that conveyed the mineral rights gave the mining company immunity. Bureau of Land Management Image.

ADVERTISEMENTBuying/selling a coal seam is much more complex than buying/selling a car. When you buy a car you simply pay for it, file a title transfer with the government and drive the car home. When the car is worn out, it goes to the junk yard and the only thing that remains is a memory. However, when mineral rights are purchased, the buyer and all future mineral rights owners will have a right to exploit the property. And, the seller and all future surface owners must live with the consequences. Usually, mineral extraction will occur at some future time. Mining companies often schedule their equipment and employees years in advance. Or, the mining company might purchase the property as a future "reserve."

It is also possible that the new mineral owner has no intentions of production. They are simply buying the property as an investment. Their goal is to sell the mineral rights to a mining company who will assume the duties of production. Speculators who have no intent to mine purchase lots of mineral properties. They are simply attempting to be "middle men" who acquire valuable property from individual owners and broker those properties to mining companies for higher prices.

(These "speculator" buyers also frequently use options. In an option transaction, they offer the property owner a small amount of money today for the option of buying the property at a specified price on or before a specified date in the future. The speculator then quickly tries to find someone who will pay an even higher price and make a significant profit. If the speculator fails to pay the specified price by the expiration date, the property owner keeps the option payment.)

When a company buys mineral rights, it also buys the right to enter the property and remove the resource at some future time. In most of these transactions, the surface owner has no say in when the mining takes place, how it will be done and what will be done to restore the property. Most disagreements between buyers and sellers occur at the time of mining. If the seller wants any control at that time, he must anticipate what might go wrong and write a contract that will preserve his wishes. Keep in mind that your grandson might own the property when extraction occurs. You were paid up front but he will live with the deal.

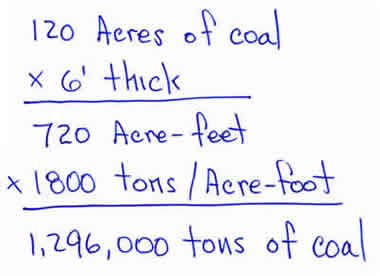

Coal tonnage estimate: How many tons of coal are down there? This is a fairly easy calculation. An acre-foot is the basic unit of measurement for coal below earth's surface. An acre-foot of coal is one acre in area and one foot thick. It weighs about 1800 tons. Calculating the number of tons of coal beneath a property involves two multiplications.

1) In this calculation we have a 120-acre property that is completely underlain by a coal seam with an average thickness of 6 feet. Multiplying the number of acres times the average thickness of the coal would yield the number of acre-feet of coal beneath the property.

2) It is known that one acre-foot of coal weighs about 1800 tons. Therefore if we multiply the number of acre-feet of coal beneath the property by 1800 tons/acre-foot, the result will be the number of tons of coal beneath the property.

The number of tons obtained in this calculation is the total tons below. The number of tons that can be recovered will be a much smaller number. Recovery rates for surface mining are often about 90%. Recovery rates for underground mining can be as low as 50% because pillars of coal must be left in the mine to support the roof.

A professional geologist or a state geological survey might be able to help you determine if coal seams exist beneath your property. They might also have an estimate of how thick those seams might be.

Sometimes a mining company does not want to purchase a property because they are uncertain of the type, amount or quality of minerals that exist there. In these situations the mining company will lease the mineral rights or a portion of those rights.

A lease is an agreement that gives the mining company the right to enter the property, conduct tests and determine if suitable minerals exist there. To acquire this right the mining company will pay the property owner an amount of money when the lease is signed. This payment reserves the property for the mining company for a specific duration of time. If the company finds suitable minerals it may proceed to mine. If the mining company does not commence production before the lease expires, then all rights to the property and the minerals return to the owner.

When minerals are produced from a leased property, the owner is usually paid a share of the production income. This money is known as a "royalty payment." The amount of the royalty payment is specified in the lease agreement. It can be a fixed amount per ton of minerals produced or a percentage of the production value. Other terms are also possible.

When entering into a lease agreement, the property owner must anticipate any activities that the lessee might do while exploring the property. This exploration might include drilling holes, opening excavations, or bringing machines and instruments onto the property. Defining what is allowed and what restoration is required is part of a good lease agreement.

Should you sign a gas lease? (Part One): A discussion of the factors landowners need to consider before signing a gas lease on their property. Featuring Ken Balliet and Dave Messersmith, both Extension Educators with Penn State Extension.

Mineral rights often include the rights to any oil and natural gas that exist beneath a property. The rights to these commodities can be sold or leased to others. In most cases, oil and gas rights are leased. The lessee is usually uncertain if oil or gas will be found, so they generally prefer to pay a small amount for a lease rather than pay a larger amount to purchase. A lease gives the lessee a right to test the property by drilling and other methods. If drilling discovers oil or gas of marketable quantity and quality, it may be produced directly from the exploratory well.

To entice the property owner to commit to a lease, the lessee generally offers a lease payment (often called a "signing bonus"). This is an up-front payment to the owner for granting the lessee a right to explore the property for a limited period of time (usually a few months to a few years). If the lessee does not explore, or explores and does not find marketable oil or gas, then the lease expires and the lessee has no further rights. If the lessee finds oil or gas and begins production, a regular stream of royalty payments usually keeps the terms of the lease in force.

Should you sign a gas lease? (Part Two): A discussion of the factors landowners need to consider before signing a gas lease on their property. Featuring Ken Balliet and Dave Messersmith, both Extension Educators with Penn State Extension.

One problem that can occur is when the lessee discovers oil or gas but has no way to transport it to market. Some lease agreements have a "waiting on pipeline" clause that extends the lessee's rights for a limited or indefinite period of time.

In addition to a signing bonus, most lease agreements require the lessee to pay the owner a share of the value of produced oil or gas. The customary royalty percentage is 12.5 percent or 1/8 of the value of the oil or gas at the wellhead. Some states have laws that require the owner be paid a minimum royalty (often 12.5 percent). However, owners who have highly desirable properties and highly developed negotiating skills can sometimes get 15 percent, 20 percent, 25 percent or more. When oil or natural gas is produced, the royalty payments can greatly exceed the amounts paid as a signing bonus.

| Stratigraphic Column |

Stratigraphic Column: The Marcellus Shale is the target of many gas wells in Pennsylvania. In some parts of the state it is immediately above the Onondaga Limestone. The Utica Shale is located beneath the Onondaga. Here is a quote from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection website that explains the significance:

"Your oil or gas could be produced or captured from a well outside your property tract boundaries. In fact, your only protection is if your oil or gas property is subject to the Oil and Gas Conservation Law, 58 P.S. § 401.1 et seq. If so, the gas on your property could be included in a unitization or pooling order issued by the Commonwealth at the behest of a producer on a neighboring tract. That well operator would then have to pay you a production royalty based on your prorated share of the production from the well, depending on how much of your tract was deemed to be contributing to the well's pool. This law applies to oil or gas wells that penetrate the Onondaga horizon and are more than 3,800 feet deep."

Image by: Robert Milici and Christopher Swezey, 2006, Assessment of Appalachian Basin Oil and Gas Resources: Devonian Shale–Middle and Upper Paleozoic Total Petroleum System. Open-File Report Series 2006-1237. United States Geological Survey. View complete stratigraphy for other areas.

Below the surface, oil and gas have the ability to move through the rock. They can travel through tiny pore spaces - such as between the grains of sand in sandstone or through the tiny openings created by fractures. This mobility allows a well to drain oil or gas from adjacent lands. So, a well drilled on your land could drain gas from a neighbor's land if the well was drilled sufficiently close to the property boundary.

Some states have recognized the ability of oil and gas to cross property boundaries underground. These states have produced regulations that govern the fair sharing of oil and gas royalties. These states generally require drilling companies to specify how oil and gas royalties will be shared among adjacent property owners when a permit for drilling is filed. The proposed sharing of royalties will be based upon what is known about the geometry of the oil or gas reservoir compared to the geometry of property ownership at the surface. This procedure is known as "unitization."

Some states do not have rules for unitization of oil and gas royalties. Other states have them but only for wells that produce from certain areas or from certain depths. These rules can play a critical role in a leasing or resource development strategy. Some people tell stories about landmen saying "Lease to me now or we will drill your neighbor's land and drain your gas without paying you a cent." In some situations, an absence of state regulations allows this to occur. If you are contacted about leasing your mineral rights, you should contact an attorney for advice on how the laws of your state will apply to your property.

(Note: In Pennsylvania the rules for natural gas sharing change at certain depths below the surface and at certain positions in the stratigraphic column. See the section labeled "Stratigraphic Column" near the bottom of this page for more information. In some areas the rules used for sharing Marcellus Shale gas can be different from the rules used for sharing gas from the underlying Utica Shale. Consult with an attorney on how these might apply to your property.)

ADVERTISEMENT

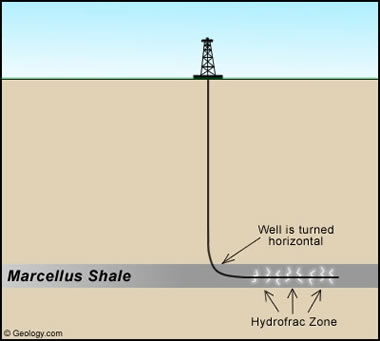

Horizontal drilling: In this illustration a well has been drilled vertically but deviated to horizontal below the surface. This type of drilling can extend the reach of a well for a mile or more in any direction. It is therefore possible to drill a well on one property and drain oil or gas from adjacent lands. How the gas and royalties will be shared is sometimes determined by state regulations and sometimes by private agreements. Regulations governing the sharing of oil and gas production vary from one state to another (and for different drilling situations within a single state). It is critical to either know the regulations or get reliable advice before entering into any oil and gas transaction.

A short story. Two men were at the hardware store and in walks a guy who asks. "Have you leased your mineral rights yet? I'll pay you $500 an acre - and write your check this morning." One man grabbed the check and ran straight to the bar. The other man grabbed the lease and ran straight to his attorney. One of these men had a million friends that night. The other had a million dollars in the bank.

Three things are required to make a successful mineral rights deal: 1) knowledge, 2) skill, and 3) patience. If your abilities fail in any one of the three, you can lose a lot of money. In a mineral rights transaction you will be dealing with a professional negotiatior with deep knowledge. If you don't have all three of the required abilities, then find a good attorney or other mineral property professional. Their assistance usually doesn't cost a lot, but the difference that they can make in the transaction can be enormous.

Anticlinal oil and gas deposit: This illustration shows a well that will produce oil and natural gas from an anticline. In this drawing we can easily see that only a portion of the surface property is directly above the oil and gas accumulation. The placement of the well is critical for proper development of this reservoir.

In addition to financial matters, a lease or sales contract can do more than simply specify the amounts paid to the owner. It can also contain language that protects the owner's property and way of life while exploration, mining, drilling and production take place. The contract can set guidelines that protect the owner's buildings, roads, livestock, crops and other assets. It can also reserve portions of the property that will not be disturbed during exploration, mining, drilling and production.

In most transactions the lessee is the one who prepares a contract for signature. If the owner signs without getting professional advice, the rights conveyed to the lessee might be greater than the owner wants to give away. Any owner who does not have knowledge or experience with mineral rights transactions should seek advice or representation from an attorney or mineral property professional. Lessees will often accept significant revisions to what is contained in their standard lease or sales contract.

Natural gas well: Drilling for natural gas usually disturbs several acres of land. A few acres are usually cleared for the drill pad. Sometimes a couple of acres are needed for runoff capture or water treatment. And, if the gas well is successful, a pipeline will be built to transport the gas to market. Image copyright iStockphoto / Edward Todd.

Disputes between the mineral rights owner and the surface rights owner usually arise at the time of mineral extraction.

These activities can require use of the surface and damage the surface owner's enjoyment of the property. Here is where the wording of the mineral rights agreement or lease agreement becomes very important. The agreement may give the mineral owner the right to extract the mineral at any time, using any methods and without compensation or regard for the surface owner. This is why legal assistance should be obtained when selling or leasing mineral rights.

When purchasing surface rights (this can be as simple as buying a home), it is a good idea to carefully examine the wording of any mineral rights agreements that apply to the property. These could grant significant liberties to the mineral owner at the time of extraction. Although you were not involved in the transaction that sold the mineral rights from the property, you will nevertheless be bound by that contract.

When you buy a property you buy both its assets and its liabilities. Hire an attorney who can do the necessary research and educate you about what you are buying.

When mineral rights are being sold or leased, the parties involved in the transaction should be in full agreement on how extraction will occur, what reclamation will be done, what equipment will remain on the property, what access will be needed by the lessee, and who is responsible for anticipated problems. Most states have mining laws and regulations that limit the mining company's actions during the extraction process and require reclamation. However, these laws might not meet the surface owner's expectations. To avoid problems these matters should be addressed in the contract at the time of sale. Again, the property owner should have an attorney who can research, negotiate, educate and ensure that the contract is appropriate.

ADVERTISEMENTDamage to the surface can be delayed. Subsidence of underground works or settlement of surface mined areas might not occur or be detected until decades after mining is completed. The owner of a fee simple estate should consider these facts before entering into a mineral rights sale or lease agreement. The consequences of mineral extraction will be passed on to heirs and all subsequent owners of the property. It is not uncommon for undermined properties to show no signs of subsidence for decades after mining is completed. Then, cracks and settlement begin to appear. In this situation the mining company may be long defunct and its owners long dead. There is no one to hold responsible - even if repair of any damage was written into the lease or sales agreement.

| What Might Be in Your Deed? |

| The language below is quoted directly from the deed of a property owned by the author, which is the location of his primary residence. This same language also appears on the certificate of title for the property. |

"Excepting and Reserving, thereout and therefrom, all the nine-foot vein of coal, iron and other minerals, together with appurtenant mining rights, as described in deed from James B. Wiggins, et ux, to Jasper M. Thompson, dated December 17, 1885, and of record in the aforesaid Recorder's Office of in Deed Book 66, page 157."

In 1885, "the nine-foot vein" was a description used for what is now known as the "Pittsburgh Coal Seam." This language conveyed ownership of the Pittsburgh Coal, iron and "other minerals" from James B. Wiggins to Jasper M. Thompson. Jasper Thompson also received rights to mine the property. It was a sale that severed mineral rights from a fee simple property.

The mineral rights transaction was done in 1885. Since then the surface property, originally owned by James Wiggins, has been subdivided many times and now is in the hands of many owners. None of those surface owners have any claim to the minerals sold to Jasper Thompson. All of them should realize that the Pittsburgh Coal has been deep mined in the area of their property.

The author has purchased mine subsidence insurance for his home from the Pennsylvania Mine Insurance Fund because he determined that his home is only a few hundred feet above the Pittsburgh Coal Seam and suspects that the coal has been mined from beneath his property. The annual premium is under $200 to protect a home valued at about $400,000.

Many households in areas where mining or drilling takes place are outside of the service of public water supplies. These property owners rely on water wells for the production of their water. When underground mining occurs beneath a property, some subsidence and settlement should be expected. If the mine is below the aquifer tapped by the well, subsidence of the mine could damage the aquifer, causing its water to drain into deeper rock units. This can cause a temporary or permanent loss of the water supply. It can also ruin the quality of the water. The value of a rural property without a water supply is a lot lower than the same property with a water supply.

When buying property in areas of potential or historic mineral development, a buyer should determine if a fee simple estate is being purchased or if ownership will be shared with others. Mineral rights transactions are normally a matter of public record, and copies of deeds or other agreements are filed at a government office.

Real estate buyers should ask the seller to specify what rights are being conveyed and have an attorney confirm that the seller owns what is being sold. In many areas the sale of mineral rights is recorded in the government record in a different deed book or database than the sale of surface property. This means that the deed to the surface property might not mention mineral rights which have been sold away. In areas of historic or potential mining activity, the buyer of a property should hire an attorney who can do this research and confirm what is being purchased. This can prevent future surprises and problems.

The mineral rights buyer probably prepared the sales agreement and prepared it so that everything will be in his favor. He wants the liberty to enter the property at any time, bring whatever equipment is needed, extract the mineral using any method, and make the minimum reclamation required by state law. A person who buys a home above these mineral rights one hundred years later will have no say in how the mineral owner uses his property as long as the mineral owner abides by the sales agreement and applicable laws.

Most states have laws that regulate mining and drilling activity. There are also laws that regulate the sale of surface and mineral property. These laws are meant to protect the environment and all parties involved in property transactions. These laws are the only protection available to buyers or sellers on issues that are not specifically addressed in the mineral transaction agreement.

Although mineral rights laws are similar from state to state, small variations can make an enormous difference when applied to individual transactions. In addition, mining and oil and gas regulations can vary significantly from one state to another. These can also have an enormous difference when applied to individual transactions. Each transaction is unique and should be carefully considered before any permanent agreement is made.

ADVERTISEMENTThe word "mineral" is used in a variety of contexts. Generally, ores of metals, coal, oil and natural gas, gemstones, dimension stone, construction aggregate, salt and other materials extracted from the ground are considered to be minerals. However, there is no definition of "mineral" that applies in every situation, and what is considered to be a "mineral" can vary from state to state and even change over time!

The amounts of money that change hands in mineral property transactions can be huge in comparison with the average person's financial experience. The total yield (lease + royalties) or mineral sale price can often exceed the value of the surface rights. Let's consider two examples:

Example A: A 100-acre property is completely underlain by a coal seam that is eight feet thick. The owner agrees to let a mining company remove the coal for a royalty of $3 per ton that will be paid upon extraction. Assuming a coal recovery rate of 90%, the owner would be paid nearly $4 million.

Example B: A 100-acre property is drilled for natural gas, and the royalties will be shared by owners of a 640-acre unit that immediately surrounds the well. The property owner is to receive a 12.5% royalty based upon the wellhead value of the gas, which at the time of production is $8 per thousand cubic feet. Assuming an average well production rate of 2 million cubic feet of gas per day throughout the calendar year the property owner would be paid over $100,000 dollars for one year of gas production.

Oil and natural gas transactions involve large sums of money, but the true value can be difficult to estimate - especially in areas where very little drilling has occurred in the past or where deep rock units are being tested for the first time.

1) Get professional assistance: Mineral rights and mineral lease transactions involve large amounts of money and are very complex. This article is intended to be no more than a brief introduction. If you are contacted about leasing or selling your mineral rights, you should promptly get advice from an attorney who has expertise in mineral transactions and the laws of your state. If you do not have an attorney, you can contact the local Bar Association for guidance.

2) The surface owner has rights: In general, the purpose of a lease or a purchase contract is to convey the rights of exploration and production to a mineral development company. However, the owner of the surface also has some rights. Basic rights of the surface owner are provided by state laws; however, every surface owner should decide if stronger protections are needed. The only way to preserve them is to be sure that the contract contains adequate language to protect crops, livestock, buildings, personal property, access and any other desires during the duration of a lease or permanently in the case of a sale. Lessees will often accept significant revisions to what is contained in their standard lease or sales contract; however, they are under no obligation to grant your requests. They can walk away.

3) Buyers and sellers beware: If you want a good financial outcome and protection for your property during and after mineral production, it is up to you and your attorney to be sure that you have a good contract. Knowledge and negotiating skills are what will determine the success of your deal. If you don't have these you are taking a huge risk.

The information above should not be considered as legal advice. It presents examples of situations that might occur when valuable commodities exist beneath the land. It repeatedly suggests seeking professional assistance if you are considering a mineral rights transaction. Geology.com does not offer that assistance or recommend people who provide it.